(photo by Graham Stanley, Creative Common License)

Are you an educator who relies heavily, perhaps mostly, possibly entirely, on lectures as your primary teaching tool?

If so, do you wonder what the point is of articles with titles such as these?

Twenty Terrible Reasons for Lecturing

Teaching More by Lecturing Less

12-Step Recovery Program for Lectureholics

Medical School Says Goodbye to Lectures

Can 800 Years of Educational Practice be Wrong?

As a faculty developer, I encounter many adherents of lecture who point to the staying power of the technique as an indication that it must be effective. Furthermore, if you attained higher degrees, employment, and substantial career achievement after receiving a strongly lecture-based undergraduate and graduate or professional education, then are you not a poster child for the educational efficacy of lecture?

In Rethinking University Teaching, education scholar Diana Laurillard nonetheless states:

“Why aren’t lectures scrapped as a teaching method? If we forget the eight hundred years of university tradition that legitimises them, and imagine starting afresh with the problem of how to enable a large percentage of the population to understand difficult and complex ideas, I doubt that lectures will immediately spring to mind as the obvious solution.”

What about that 800-year tradition? Canadian researcher Norm Friesen provides a history of the academic lecture and points out that it has not been static for 800 years. Over time he shows that lectures represent changing trans-media pedagogies, teaching where a speaker interacts with media. Prior to the printing press or widespread availability of books, lectures were events of reading authoritative texts to an audience. Indeed, the word “lecture” emerges from Medieval Latin roots meaning “to read”. When books became readily available, lectures focused on an authoritative speaker presenting and explaining what was in the printed books – a transition from text as authority to speaker as authority. In later centuries, lecturers engaged with other media during their presentations: Chalkboard, slides, overhead transparencies, and eventually PowerPointTM. As lecturers engaged with media other than books they were less likely to read a lecture and to more likely use what noted sociologist Erving Goffman calls “fresh talk” where the spoken text is formulated by the lecturer moment to moment. Both Friesen and Goffman see the modern lecture as turning text into an event and at least an impression of conversation between speaker and audience, even if almost entirely one-sided. However, what remains in all of this history of change in lectures is the idea of the lecturer as an authority and the source of knowledge or the skillful presentation of that knowledge. Friesen misses the irony of the typical academic PowerPointTM lecture where the speaker ostensibly reads bullet lists of text from his or her slides, coming full circle back to reading a lecture.

A 14th century lecture at the University of Bologna, painted by Laurentius de Voltolina. Notice the distracted and sleeping students. (Public domain)

Indeed, the lack of learner engagement in the university lecture classroom, which is at the root of Laurillard’s criticism, is a long-recognized problem. In 1927, Henry Lloyd Miller noted:

“Lecturing is that mysterious process by means of which the contents of the note-book of the professor are transferred through the instrument of the fountain pen to the note-book of the student without passing through the mind of either.”

This concern about lack of thoughtful engagement with the content by the learner remains today as research shows a preponderance of “notetaking” on laptop computers that borders on verbatim transcription of the lecture.

If lecturing originates from reading a text, then what did education look like before there was text to read? The Greek School of Athens provides an example, as represented more a millennium later in a fresco (below) by Raphael. This environment resembles more closely the active-learning classrooms that emerged in the last two decades to focus on learning activity, problem solving, and small-group discussion.

Active learning in the School of Athens as painted in a 1511 fresco by Raphael. Plato and Aristotle are the central, walking figures. Socrates, in the olive-green robe left of center is engaged in dialogue with learners. (Public domain)

Does the recent popularity of active learning represent a throwback to antiquated education methods? Why did the Medieval lecture tradition replace earlier active learning? Malcolm Knowles, renowned for the advocacy of adult learning principles known as andragogy, offered this explanation for the demise of superior active-learning approaches:

“I believe that the cultural lag in education can be explained by the fact that we got hemmed in from the beginning of the development of our educational system by the assumptions about learning that were made when … education … became organized in the Middle Ages. Tragically, the earlier traditions of teaching and learning were aborted and lost with the fall of Rome; for all the great teachers of ancient history – Lao Tse and Confucius in China, the Hebrew prophets, Jesus, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Cicero, Qunintilian – … made assumptions about learning (such as that learning is a process of discovery by the learner) and used procedures (dialogue and ‘learning by doing’) that came to be labelled as ‘pagan’ and were therefore forbidden when monastic schools started being organized in the seventh century.”

The Illusion of Learning

Nonetheless, lecturing has persisted since the founding of the earliest European universities. To some extent, this is probably because of the familiarity of the approach that is transferred from one generation of educators to another through the teaching process. Generally untrained in education theory, university faculty teach as they were taught. Grabbing onto the role models and examples from their own education, faculty members continue the tradition of authoritative delivery of information to a listening, note-taking, and only occasionally participating, audience of learners. Students, for their part, are accustomed to the lecture and at least tolerate it if not expecting it. At the same time, faculty commonly complain about low attendance at their laboriously created lectures. What makes a lecture unmissable? A survey of geography students revealed that nothing short of active participation in learning would improve attendance in class.

I suggest that the persistence of lectures, in large part, relates to an illusion – on the part of both teachers and learners – that the polished lecture does generate learning. For instance, Iowa State University psychology researchers conducted an experiment where two groups of students received the same topical lecture by the same presenter. In one group, the professor presented with all of the hallmarks of a very fluent public-speaking performance, whereas she provided a disfluent, disorganized, lecture to the other group. In immediate post-lecture surveys the students evaluated the lecture performances as distinctly excellent and poor, respectively. When asked to estimate their test scores on the presented material, the attendees of the “excellent” fluent lecture predicted an average score that was twice that of the students attending the “poor” disfluent lecture. Then the test was administered with identical results for both groups. The students attending the fluent lecture perceived they were learning because of the quality of the lecture, but they really did not (with potentially interesting implications for the inveterate lecturers who defend their practice by the high teaching ratings they receive from students). As Goffman points out, lectures are fundamentally a performance and if the performance is good, the audience at least pays attention but that does not mean that they are learning.

Why are they not learning? Again, the answer has been known for a long time. In his inaugural address as president of Harvard University in 1869, chemistry professor C. W. Eliot made this metaphorical observation:

“Recitations alone readily degenerate into dusty repetitions, and lectures alone are too often a useless expenditure of force. The lecturer pumps laboriously into sieves. The water may be wholesome, but it runs through.”

The wholesome watery knowledge runs through because it is not manipulated in working memory. Cognitive psychology research reinforced with neurological imaging shows that sense making of new information takes place through doing something with that information and connecting it with prior knowledge. If lectures are primarily stimulating auditory and visual senses and promoting note taking without cognitively manipulating the content, then a memory is not formed; the knowledge flows through the sieve and is not retained in long-term memory.

Nonetheless, learning has happened during the centuries that lecture dominated university instruction. However, very little of that learning occurs during the lecture. It happens when learners pursue homework problems, write papers about the content, study notes and texts (alone or with peers), and seek learning assistance during one-on-one tutoring and instructors’ office hours. In all of these cases, working memory is engaged and manipulating the new knowledge, hence learning takes place. Therefore, if lecture does not promote much learning, should that class time be better used? Given the ready access to information, in multiple media formats that did not exist when the lecture tradition began, is scheduled class time really best used with transmission of information from the teacher to the notetaking learner? That is the point that Diana Laurillard raises in the quote near the beginning of this essay. If we want to maximize learning, would we really select lecture as the optimal process?

The Evidence against Lecture

A large body of literature supports the conclusion that college students learn better from a variety of active-learning strategies (e.g., cooperative learning, peer instruction with audience-response systems, team-based learning, problem-based learning, etc.) than during lecture. A research team led by Scott Freeman at the University of Washington conducted a meta-analysis of 225 such studies in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and showed stronger learning gains and lower course-failure rates when instructors utilized active learning. These authors emphasized the significance of these results by metaphorical comparison to medical trials:

“If the experiments analyzed here had been conducted as randomized controlled trials of medical interventions, they may have been stopped for benefit—meaning that enrolling patients in the control condition [lecture] might be discontinued because the treatment being tested [active learning] was clearly more beneficial.”

In reviewing the Freeman et al. study, physics Nobel-laureate Carl Wieman, and former Associate Director for Science in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, was much more blunt than Laurillard:

“This meta-analysis makes a powerful case that any college or university that is teaching its STEM courses by traditional lectures is providing an inferior education to its students.”

Wieman’s assertion takes on even more importance when we realize that lecture-focused instruction may be unintentionally discriminatory. Research by Nicole Stephens at Northwestern University argues that the focus on competition, independence, and teacher-as-authority that prevails in higher education runs counter to the epistemology of first-generation college learners from working-class backgrounds. Not surprisingly, then, comparing learning outcomes of biology students experiencing a dominance of lecture or active-learning instruction shows not only greater learning for all students with active learning but disproportionate gains for first-generation students and students of color, so as to substantially diminish well-known achievement gaps.

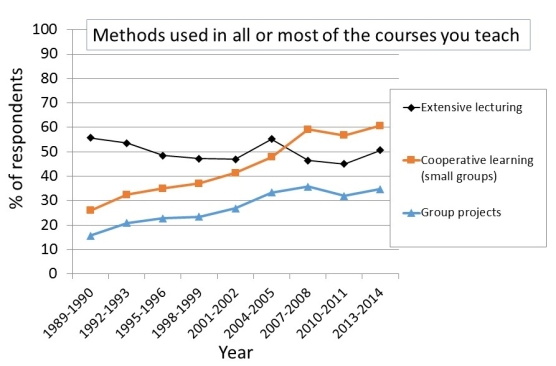

The research evidence favoring active learning, along with faculty members’ perception of improved student learning and greater enjoyment in teaching, may explain the increasing use of alternatives to lecture. Biennial surveys of full-time undergraduate faculty at American universities and colleges by the UCLA Higher Education Research Institute shows dramatic increase in the use of cooperative-learning and group projects and a slight decrease in the use of lecture as a primary teaching method. Furthermore, active-learning approaches are used most by assistant professors and least by full professors, suggesting the possibility of gradual changes in pedagogy in the future.

Surveys of faculty teaching undergraduate students show a marked increase in the utilization of active learning and a slight decrease in reliance on lecture during the last 25 years. (Data from HERI)

Why Don’t Lectures Die?

Despite the evidence favoring less use of lecture-focused instruction, the graph above shows that lectures have staying power. Some of this resilience likely rests with inertia and familiarity. I have anonymously surveyed more than 400 faculty members at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, mostly during new-faculty orientation, regarding their perceptions of the active-learning versus lecturing as the best way to generate learning. Only 6% accept that lecture is best while 88% advocate for active learning and the remaining 6% claim that there is no difference. Yet, we know that most of these faculty members will extensively use lecture . Largely, they admit, because it is easiest and does not threaten their confidence that could arise by utilizing unfamiliar alternative appoaches. Others attempt active learning but are discouraged when not obtaining results comparable to the Freeman study.

Likewise, I have anonymously surveyed more than 400 medical students during their orientation. By a ten-to-one margin, they acknowledge active learning is superior to lecture. Yet, when asked which approach they prefer, 52% select lecture. Why would students prefer a format of learning that they feel is inferior to their learning? During discussion, they point to the many prior experiences of poorly designed and executed active-learning assignments that did not generate learning, and the undependable nature of classmates who did not arrive prepared to participate with group learning. These opinions also appear in research on medical students’ attitudes toward active learning. From a faculty standpoint, there is need to improve the implementation of research-based teaching practices. From the learner standpoint, there is need to take more responsibility for one’s own learning; the type of self-regulated, engaged, and commonly collaborative learning that will dominate their career and professional development when they will not be listening to academic lectures.

Which brings us back to the title of this post, which is a playful modification of the common proclamation upon the accession of a monarch. One dies but the institution continues. The data argue for replacing lecture and this need has been recognized for more than a century. Nonetheless, the institution continues. Do you want to know more about shifting your teaching away from over-reliance on lecture and also getting learner buy-in along the way? Check with your faculty-development professionals for guidance and seek out colleagues who will welcome you to observe their active classrooms. Bloodletting persisted for 2000 years, even continuing after killing George Washington, and lecture may persist as long but that does not mean we should ignore research-based teaching methods.

By Gary A. Smith, Assistant Dean of Faculty Development in Education and Director, Office for Medical Educator Development, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

![]()